#33 How the 5 stages of grief became a rulebook that misses the mark

The untold story behind the grief model we rely on — and why it’s time for something different

If you’re new here, welcome to Grieve Fully, Live Fully — a space for honest, heartfelt reflections on grief, growth, and the messy, beautiful middle of being human. Whether you’re navigating loss, facing life’s uncertainties and challenges, or simply seeking a little hope, you’re not alone.

I’m Ruhie — writer, doctor, mum & grief advocate. I don’t have it all figured out, and you don’t need to either. Let’s walk this path together with honesty, intention, and compassion.

When you lose someone you love, you crave anything to help make sense of the chaos. That’s often when the five stages of grief show up: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance.

Maybe someone handed them to you in a pamphlet when your world had just turned upside down.

Maybe you found them in a bleary-eyed 2am Google search, desperate to know if what you’re feeling is normal.

I first heard about them in medical school — a few clinical lines skimmed over in a psychology tutorial.

At first glance, they seem helpful. Predictable. Comforting, even. But when I experienced deep loss firsthand, I discovered that grief is far messier than five neat stages.

This post is about pulling back the curtain on the framework so many of us have heard about and come to rely on in our grief journey — where it came from, how it’s been widely misunderstood, and what it leaves out.

Because, while the stages have some utility, they don’t come close to explaining the full, complicated reality of what it means to lose someone you love.

The Origin Story

The 5 stages of grief were developed by psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross in her groundbreaking 1969 book On Death and Dying. Here’s the part most people miss: she created the model while working with people who were dying, not those left behind.

They were originally meant to describe how people come to terms with their own terminal diagnosis — that is, a way of understanding anticipatory grief.

The five stages were never intended to be a universal formula for how everyone grieves every loss.

This is an important distinction that Kübler-Ross herself later clarified. She acknowledged that grief is deeply individual and not everyone goes through all five stages or in any particular order.

So, What are the 5 Stages of Grief?

In case you aren’t familiar with them, here’s a quick breakdown:

DENIAL:

This is the mind’s way of cushioning the blow — the disbelief, shock, or numbness that follows a major loss. After my dad died, I felt like a robot for weeks, going through the motions without really feeling anything. That shock and numbness were overwhelming, but they also shielded me from facing all the pain at once.

ANGER:

Grief often brings waves of anger — frustration, resentment, or even rage — at the situation, other people, the person who died, or even ourselves. It’s a natural response to the unfairness and pain of loss. For me, anger took many forms and surprised me with how raw it felt: bitterness toward those still with their loved ones, fury at how unjust everything felt, and most of all, anger at myself for what I should have done differently.

BARGAINING:

This stage is full of “what if” and “if only” thoughts — desperate attempts to make sense of loss or imagine alternate outcomes. Even though deep down I knew replaying those moments wouldn’t change anything, I kept getting caught in endless cycles of self-blame and regret.

DEPRESSION:

When the weight of the loss truly sinks in, deep sorrow follows — feelings of emptiness, loneliness, and profound sadness. This was the stage I expected most, but it still hit me hardest. Life felt empty without my dad, and the hope and warmth he brought into my life vanished, leaving me in a darkness I hadn’t known before.

ACCEPTANCE:

This doesn’t mean the pain disappears or that you’re ‘okay’ with the loss. It means acknowledging the reality of what happened and starting to live alongside it. For me, acceptance arrived slowly over time, in small everyday moments: laughing again, feeling joy, letting others in, and slowly rebuilding my life while keeping Dad’s memory alive.

Each of these stages represents the most common emotional responses to grief — but they’re not universal, and they’re definitely not linear.

The Misinterpretation

Somehow, over the years, the five stages morphed from one framework for understanding anticipatory grief into the only way to explain all grief. It became a checklist — printed in brochures, taught in training programs, shared on social media. But often without the nuance or context they require.

The result? Many grievers (myself included) are left wondering if we’re doing it ‘wrong’.

“I never felt denial. Is something wrong with me?”

“I thought I had accepted it, but now I’m angry again.”

“Why am I still sad months — or even years — later?”

We internalise the idea that grief should follow a predictable path. That if we can just make it to acceptance, we’ll be ‘done’. But grief doesn’t work like that.

What It Misses

The five stages model leaves out much of the true complexity of grief:

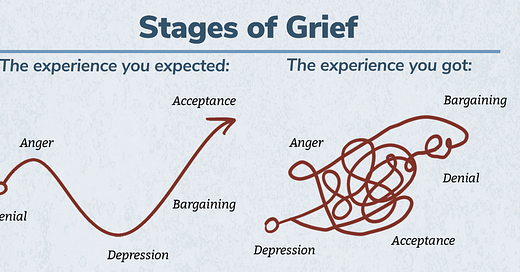

Grief isn’t linear: we don’t move neatly from denial to acceptance in order. We move back and forth, sometimes experiencing multiple emotions all at once.

Grief is deeply personal: the presence, intensity and duration of each stage vary widely from person to person. Not everyone will experience all five stages, and not always in this exact sequence.

There’s many other feelings and phases beyond these five: the model oversimplifies a much broader emotional experience.

Grief can reemerge unexpectedly: triggered years later by a birthday, a photo tucked away in a drawer, or simply on a random Tuesday afternoon in the supermarket when a song suddenly reminds you of them.

Emotional duality: the fact that joy and sorrow can coexist.

The role of culture, personality, trauma, and relationships: all of which shape how grief is felt and expressed.

Grief isn’t a checklist. It’s a landscape. One we learn to navigate over and over, often with no map.

What We Can Still Take From It

That said, the five stages aren’t useless. They can give shape to something that feels overwhelming.

When my dad died, it was the first big loss I’d ever experienced. I had no precedent to follow; no blueprint that told me what ‘normal’ grief was supposed to look like. My cousin gave me Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s book soon after his passing, and in those early weeks, it felt like a lifeline. For the first time, something gave language to what I was feeling. When I was numb and disconnected, or furious and deeply ashamed of it — reading about the stages reminded me I wasn’t broken. That these feelings were all valid and natural parts of grief.

But the comfort didn’t last. I’d feel acceptance one day, only to crash into a wave of anger or despair the next. I started wondering: was I grieving wrong — or was the model too neat for something this messy?

The reality is, the stages aren’t milestones to unlock. Grief isn’t a Super Mario game where you clear one level and move on to the next, celebrated by a catchy jingle (clearly, I’ve been influenced by my Mario-obsessed kids!)

A More Holistic Way to Look at Grief

We need a way of understanding grief that reflects its complexity — its ebbs and flows, its unpredictability, its depth.

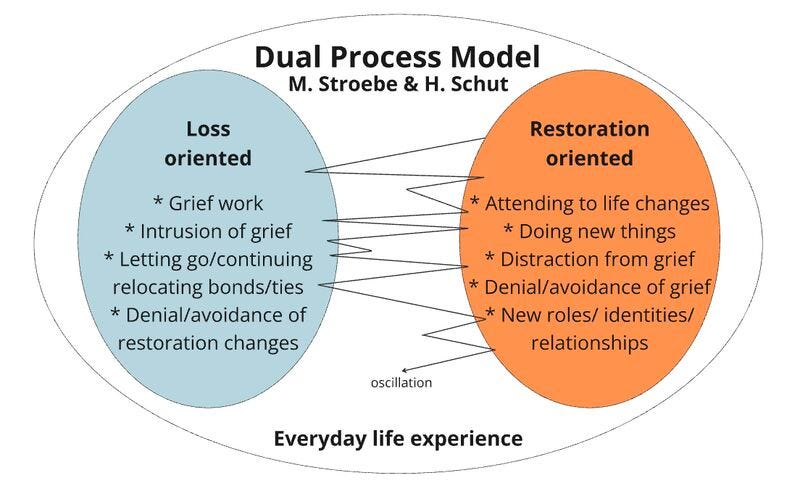

One model that offers this is the Dual Process Model of Grief, developed by psychologists Margaret Stroebe and Henk Schut. It recognises that grieving isn’t just about processing pain — it’s also about learning to live in a changed world.

The model describes two types of coping:

Loss-oriented coping, which involves confronting the pain of the loss — the sadness, the memories, the longing.

Restoration-oriented coping, which focuses on adapting to life after loss — handling practical changes, building new routines, and rediscovering meaning.

What makes this model powerful is the recognition that healthy grieving involves oscillating between these two modes — turning toward the pain sometimes, and turning away at other times to engage with life again.

For me and for many others, this framework feels far more compassionate and realistic. It makes space for the full emotional rhythm of grief and reminds us that healing doesn’t mean forgetting; it means learning how to live with both love and loss, side by side.

The Upshot?

The five stages model doesn’t capture the messy, non-linear, deeply personal experience of grief — nor was it ever intended to.

It gave us a way to begin the conversation. But now, we need to keep it going. By sharing our stories. Listening without judgment. And letting go of the idea that there’s a ‘right’ way to mourn.

When we talk honestly about grief, we feel less alone. We help each other carry it.

Not perfectly. Not in stages. But together.

Thanks so much for reading!

Until next time,

If this resonated with you, I’d love to hear your experience.

Did the five stages reflect your experience of grief — or did they feel too simplistic? What helped you better understand your grief journey?

Thank you for being here and supporting my work. I am truly grateful!

If you got value from this and you think others might too, please:

1️⃣ Click the HEART button 💟 to like this post and leave me a COMMENT 💬 — it means we can connect on a deeper level and allows my writing to reach more people who need it

2️⃣ SUBSCRIBE for free to “Grieve Fully, Live Fully” — a supportive space to help you navigate loss, embrace life wholeheartedly, and find strength through life’s challenges

3️⃣ SHARE my newsletter with someone you think would appreciate it

4️⃣ And don’t forget to

🌈 Live Fully

💛 Love Deeply

😁 Laugh Often

⏳ Make the most of the time we are given

I'm glad you wrote about this, Ruhie. In my book, From Grief to Grace, I explained that the 5 stages of grief were intended for the terminally ill, not for everyone.

Thank you for the clear, simple explanation of what Kubler-Ross' stages are and aren't. When I read an article or book on grief and the author misrepresents her work, I tend to discount the rest of what they say. I understand why people want to believe grief is linear and predictable. Human beings like simple models. Our brains crave predictability, which is one reason we have so much trouble with grief. As you said, our feelings come and go seemly at random, often when we are completely unprepared for them.

My biggest problem with the 5 stages is the misunderstanding that once you finish one, you never go backwards, when really grief is two steps forward, one back. I assume this is also true with anticipatory grief. Just because I accept my new reality today, doesn't mean I won't get slapped right back into denial or anger tomorrow.